Editor’s Note: Bill and Denise Semion are members of LTV’s sponsored content team, The Leisure Explorers. Do you own a Leisure Travel Van and enjoy writing? Learn more about joining the team.

A Sobering Journey from Selma to Montgomery

Sometimes, trips are for fun. Sometimes, for relaxation. Or both. And sometimes, they are an opportunity to learn and contemplate things that perhaps we don’t want to confront. But we go, because something simply compels us to. That was the case this spring while returning to Michigan from Florida.

There’s a new memorial to peace and justice, and injustice at the same time, all along a 54-mile stretch of US 80 between Selma, Alabama, and Montgomery, Alabama, as well as in both cities.

Yes. That Montgomery, and that Selma. If you’re of an age, you remember those epicenters of so much pain and triumph during the civil rights struggle in the 1960s.

I was a teen during the 1965 Selma to Montgomery freedom march and “Bloody Sunday”, and the violence and death surrounding it. I also remember news stories about the famous Montgomery bus boycott of the late 1950s that gave momentum to the civil rights movement of the past century. Those memories drove me, literally, to see where it all happened and to touch a part of American history.

If your travels take you south, I urge you to follow us at some point. But, prepare yourself for a range of emotions. It may be one of the most somber, sad, stirring, frustrating, enlightening, and ultimately inspiring journeys you’ll ever take. If you’ve never heard of the events that happened there, you will be shocked. Guaranteed. If you have heard of the events, you will be shocked. Guaranteed. You will be chastened. You will experience emotions you may have never felt before.

You will hear the ghosts of those who experienced what happened here if you let them speak; if you will feel, see, and imagine. Hear the whispers and the shouts when you learn what happened here both a short 55 years ago and hundreds of years ago, reaching back to what some call America’s original sin. Hear the echoes bounce, careen, crash into, and set off a chain of events leading up to today. Listen, and you will learn, if you allow it. The journey may make you uncomfortable. So may this article. But both will hopefully make you think.

Selma

This is where it began in 1965. Downtown, which has seen far better days, and far worse for that matter, includes an interpretive center for the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail. What happened in the South propelled the civil rights struggle forward shortly after Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act. But it was not enough.

At Brown Chapel, a statue stands honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and others, including the late Rep. John R. Lewis, who planned a march to Montgomery 54 miles east following a series of previous clashes with authorities.

The month-long trial of wills and history began with the killing of a Black man by police. That death and two others would shine a national light on Alabama and neighboring states, exposing the need for more action.

The church is a few blocks from a quiet park next to the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Named for a Confederate general, senator, and KKK Grand Dragon, that bridge is also historic. Park across from the Selma Interpretive Center and walk the bridge. On March 7, 1965, Lewis and others left on the first march attempt, which culminated in Bloody Sunday when state troopers and others attacked. It took a second march and a second death to bring about the next attempt on March 21, this time protected by federal troops.

Now, drive the route. Signs along the way denote where up to 2,000 people overnighted at makeshift camps on the land of sympathetic farmers and alongside country stores, many of them Black-owned. About 20 miles east of Selma, look for a simple country church and memorial at the top of a rise.

It’s for Detroiter Viola Liuzzo, who was shot and killed while transporting some of those who had marched along the highway. Her death, the third, stirred Congress to act and President Johnson to sign the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The memorial is also near the Lowndes Historic Trail Visitor Center. It was closed due to COVID on our visit, but it’s definitely worth a stop.

Overnight at Gunter Hill Corps of Engineers campground along the Alabama River to be in Montgomery early.

Montgomery

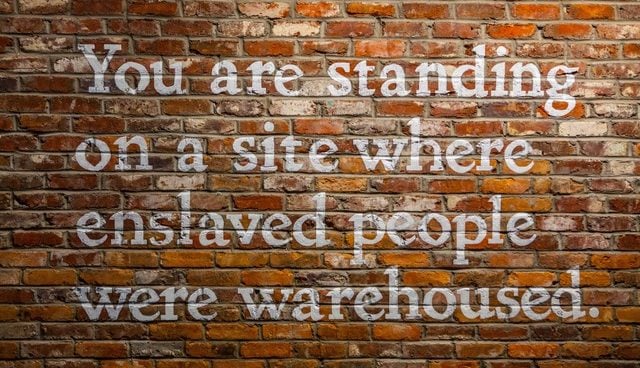

Make downtown your first stop in Montgomery – it’s a primer to what you’ll see later. We first toured the Legacy Museum, one of the sites funded by the Equal Justice Initiative. The Initiative was founded by lawyer Bryan Stevenson, whose work was depicted in the book and movie Just Mercy. Your visit to the Legacy Museum begins with a stark reminder of the recent past, then takes you on a journey of discovery of things you may not have known or realized about America’s “peculiar institution” of slavery.

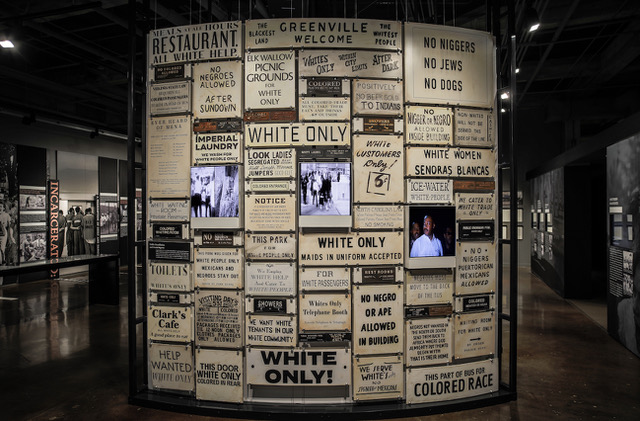

Step inside and prepare to learn – and cringe at learning – that you’re standing on a site where slaves were imprisoned in a city that was one of the largest domestic slave markets in the South, and the largest in Alabama. Displays include signs that were common across the South less than a half-century ago, and a striking sculpture, Doubt, by artist Titus Kaphar. It’s why this part of the region was nicknamed The Black Belt. You’ll learn, or be reminded, that slavery really didn’t end with the Civil War. It simply evolved – into sharecropping, for example, with the same relationships and results. It’s why this and neighboring states became the center of the civil rights struggle in the 1960s. The museum’s displays include news clips from that time and Dr. King making a case for his views that are especially relevant now. They argue that, while the name and techniques for keeping one race or another under the yoke may change, the result is the same.

Those roots of 400 years of slavery began only a few blocks from where the Museum stands. The slave market sales block is now strangely adorned by a fountain. When you’re here, you are surrounded by former slave auction sites. Yes, things have come a long, long way. But here and elsewhere, you’ll come away thinking it’s got a long, long way to go.

Back outside, grab some lunch, perhaps at Dreamland BBQ around the corner, digest what you’ve seen, and prepare for more.

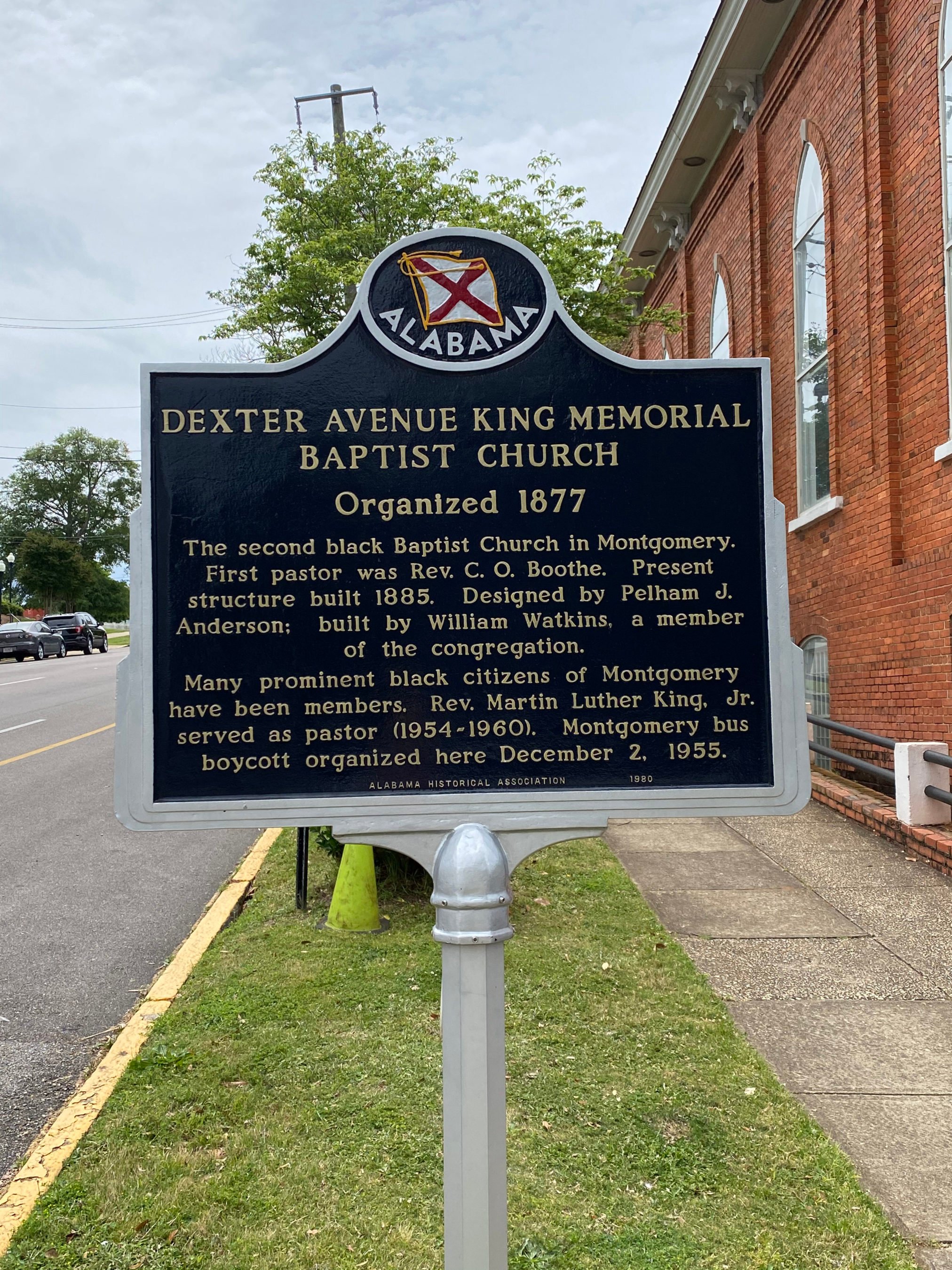

Drive by the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, where tourists stand on its arching stairs. It was here that King planned the Montgomery Bus Boycott that made him and others – including Claudette Colvina and Rosa Parks – known worldwide. The fact that the church is just steps from the Alabama Capitol Building where Governor George Wallace held forth just a few years later, two years before the march from Selma, is ironic. This choice of location to plan the boycott was perhaps meant to send a signal to the South’s Old Guard: Times are changing.

Two minutes around the corner is the parsonage where King and his family lived and were bombed during the boycott. A statue of Parks is downtown, at the spot where it’s believed she boarded the bus that was the spark that began the boycott. She’s looking at the fountain where slave auctions took place.

National Memorial For Peace and Justice

It’s jolting. And it’s meant to be. It’s just a few blocks away, so you’ve got little time to prepare.

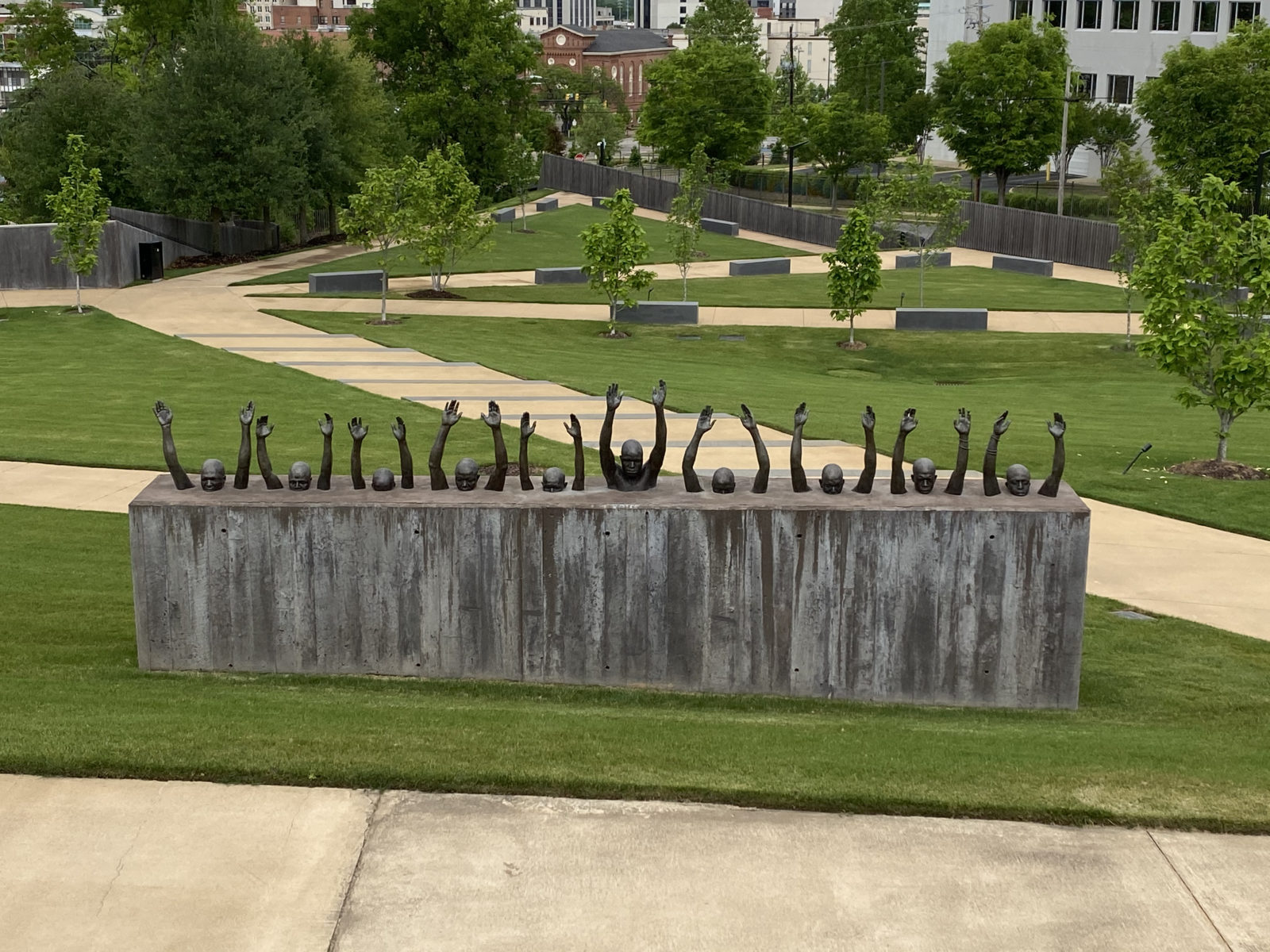

The walk up a ramp to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice includes sculptures and a memorial peace garden. You arrive at a stark, rectangular memorial with hundreds of clay-red metal rectangles, arranged by state. Each is inscribed with names and dates. No walls. A fountain in the center. A graveyard feel. Sadness. And with a peace garden outside.

This is a memorial to more than 4,400 African American men, women, and children killed by white mobs in 12 states between 1877 and the 1950s. Most were hanged. Some were shot and burned and then hanged, a message to Black people and sympathizers at the time. But today, it is a message for everyone, a message that’s been transformed here, in the epicenter of the civil rights struggle.

Walk through the exhibit. The steel takes on human form, strung from the ceiling by thinner steel columns eerily depicting ropes. On each plaque are names and dates of the dead.

I asked one docent how he was able to work here with these visible collective memories everywhere. He sighed heavily, physically acknowledging the weight of what we stood under. I asked about the reaction of visitors here. He sighed again, and began.

“There was a woman who visited here. She was 92. She was walking through. She just happened to look up. She saw the name of her brother. No one had known what happened to him until then. No one. He’d just disappeared. He was killed one state away.”

We both were silent, grasping the power of that moment and what it meant, through the centuries of slavery and war to that day.

Remember that when you come here. When you walk through the blooming peace garden. When you walk among the names. Ask yourself, were you prepared to come here?

What have you learned from Selma to Montgomery?

What have we all learned?

How did you feel?

How do you feel now?

How do we all feel?

So, what’s the message, ultimately? That’s up to you. It may be to learn that we’ve come a long way, as much of the south has. It may be that we’ve got a long way to go.

Perhaps the message is all the above. Reflection, however, is always the first step towards truth, recognition, and reconciliation.

When You Go

Begin your journey at the National Park Service’s Selma to Montgomery trail website. From there, visit Montgomery’s Legacy Museum and Memorial and the National Center for Peace and Justice.

Comments