Editor’s Note: Bill and Denise Semion are members of LTV’s sponsored content team, The Leisure Explorers. Do you own a Leisure Travel Van and enjoy writing? Learn more about joining the team.

Their Journey Took Two Years; You Can Do It in About Seven Weeks

On our most recent road trip, I finally began reading a book that has been in our 2015.5 Unity Murphy Bed since the day we bought it: The Journals of Lewis & Clark.

The two leaders of The Corps of Discovery (which consisted of up to 52 men and for much of it, one woman, Sakakawea) walked, paddled, rowed, rode, and sailed across what was then the newest portion of the US, starting even before ink was on the Louisiana Purchase. Among their goals: find the source of the Missouri River and reach the west coast to claim that disputed area for the US.

It took two years. Two years of mosquitoes (they spelled it 26 ways), chasing and being chased by grizzly bears, (they called ’em white or brown bears), getting lost (they’re forgiven; I mean, they spent two years traveling through land most Europeans had never seen), and maladies ranging from infections to a member’s unfortunate death (probably from appendicitis). Add a winter spent on the rainy west coast in a log fort and some pretty amazing “by guess and by golly” orienteering back and forth across the continent, and historians have called it one of the most amazing feats of the 19th century and American history.

You, on the other hand, can do it comfortably in a few weeks, or in our case, over several different trips, each time either following or crossing their route on our way west and back to our home state of Michigan. We’ve taken that book nearly everywhere they traveled, excluding a small stretch of eastern Washington and the place where the Missouri enters the Mississippi.

So while Meriwether Lewis and William Clark (I’ll shorten to L & C) had a tougher and in many ways scarier time than you will, here are some of the highlights of how you can follow along on their exploits, encounter your own adventures, and only imagine what they both endured and enjoyed.

Fortunately for us, the 200th anniversary of their trip brought a lot of activity, including construction of visitor centers, as well as lots of information online about the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail. The Trail covers 16 states, including the 10 the Corps traveled through. Following are some of the highlights you can enjoy.

Picking Up the Trail

Instead of starting where they did, just upriver from St. Louis, Missouri, we encountered our southernmost brush with their route along the Missouri River near Columbia, Missouri. It was an overnight stay at a nightmare of a private campground that’s closed now and shall remain unnamed. But, it’s along Katy Trail State Park, a 240-mile hike/bike route across the state.

We met up with the Trail again mostly recently near Omaha, where the already broad river takes a decided bend north near the National Historic Trail Headquarters. Today, I-80 crosses the river and above it a restored Union Pacific Big Boy steam locomotive, the largest ever built, can be seen at Kenefick Park.

Follow the river northwest through South Dakota and you’ll arrive at the state’s capital, Pierre, and the giant Oahe Dam. Farther north, you can camp overlooking the river a few miles outside tiny Akaska at Swan Creek Recreation Area (power is available here). Move north through Mobridge (combine Missouri and Bridge), then take a little detour to see the Sakakawea Monument looking over the river (see Sitting Bull here, too, where I had an interesting metaphysical experience), then perhaps stop at West Side Meats to fill the freezer with locally raised buffalo and other wild game at great prices.

In a few more miles, you’ll be in North Dakota. Next major stop: the capital, Bismarck. Mandan is just across the river. Walk the ground where the party passed On-A-Slant Village – built on the river’s western banks that slant towards the river – on their way to their first winter quarters with the Mandan people, north of Bismarck in present-day Washburn (population 1,200).

Bismarck is a must-stop for two big reasons. The restored On-A-Slant Village is a great stop to view what the lodges of these farmer/traders were like before they abandoned them to move north to Washburn following quarrels with the Lakota Sioux. Second, it’s also adjacent to Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park.

The park not only has camping along the Missouri, but Fort Abraham Lincoln is where Custer left from and never returned, meeting his fate at the battle of Little Big Horn to the West in present day Montana. The partly reconstructed fort’s commandant quarters, where Custer’s wife heard the news about her husband, is open for tours. Bismarck also has its own L & C Interpretive Center.

Tiny Washburn to the north is home to another large L & C Interpretive Center. It is about two miles from the reconstructed Fort Mandan, where the Corps stayed until April 1805. At this time, amidst cold and snow, they set out west on the river with the help of their newest companion, Sakakawea. Lake Sakakawea, the fish-filled, 180 mile-long lake that bears her name, is a few miles north, formed by a dam at Garrison, North Dakota. Camping is available near Washburn and along the lake.

The party, heading west, continued into present-day Montana, following the Missouri upstream and over the falls at Great Falls. The falls were actually a series of cataracts, which are still there, kind of – they’ve since been tamed by dams. One can only imagine what the Corps felt when they first heard, then saw, the falls.

Move farther upstream and the terrain becomes mountainous, with the river here famed for trout fishing, especially near the small community of Craig (population 43). There are at least six fly shops or guide services in the seven miles between Craig and the community of Wolf Creek upstream. That should tell you something about the fishing on this stretch!

We came this way tracing the L & C route backwards from the Livingston/Bozeman area before heading to Glacier National Park. On the way, we stopped for lunch at Yorks Islands fishing access site, named for York, a member of the Corps of Discovery who was also Clark’s slave.

At Three Forks, the Madison and Gallatin Rivers, flowing from Yellowstone National Park, meet the Jefferson River to form the Missouri at Missouri Headwaters State Park, which has a 17-site campground. On arrival here, the party had made it. They’d traveled many months and 2,500 miles; we made it here from Michigan in a leisurely week or so.

The Park is west of Bozeman, home of Montana State University and the Museum of the Rockies. Around here, your route can also include a trip over Bozeman Pass between two of my favorite Montana towns, Bozeman and Livingston. Clark passed over the Pass on his return trip after he and Lewis separated to explore different areas. You can also take the Pass via I-90.

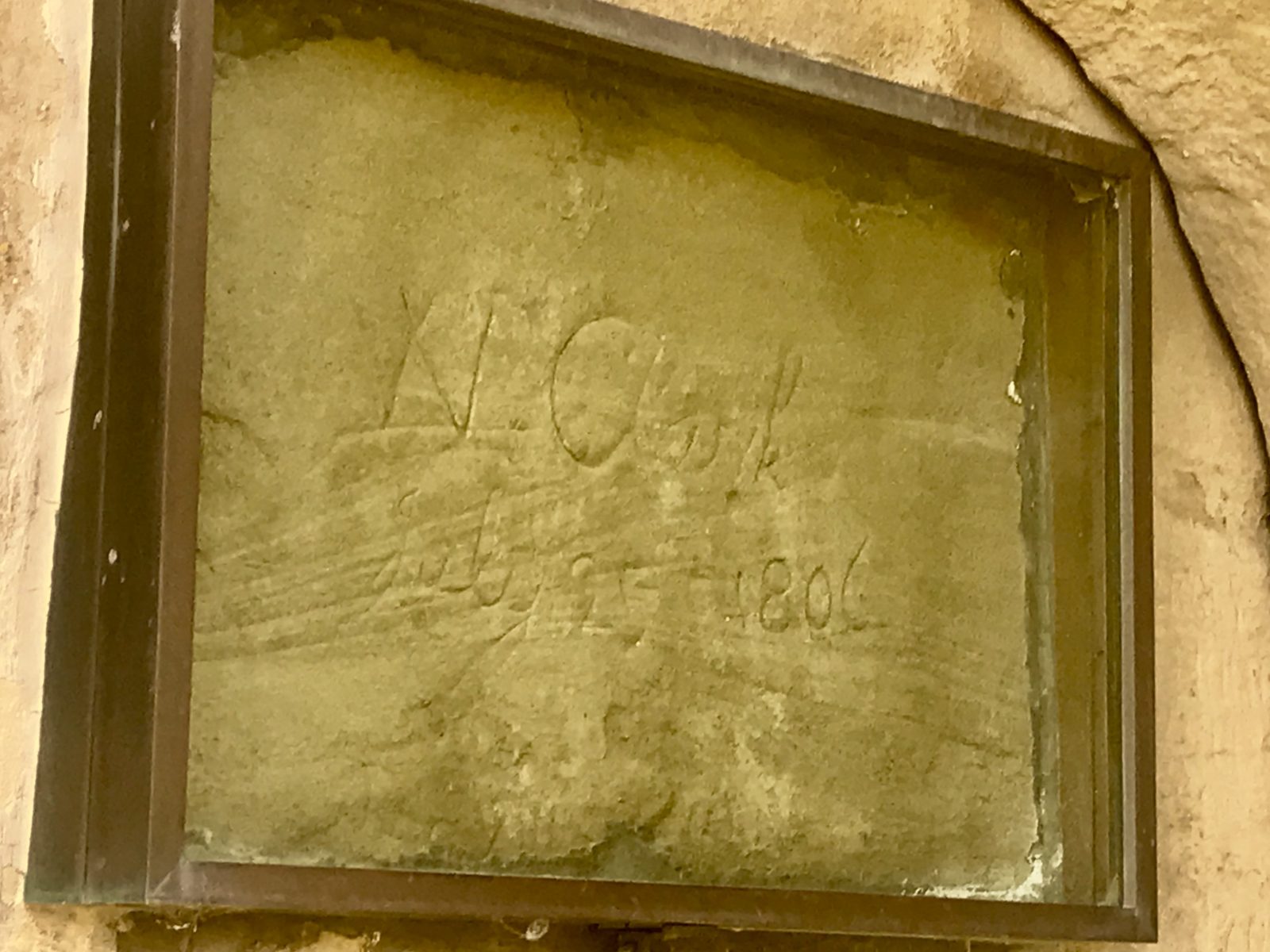

Clark followed the Yellowstone River east from the Livingston area. The Yellowstone is the last major undammed river in the Lower 48. Along the way, he passed a sandstone outcropping east of present-day Billings, Montana, that he named Pompeys Pillar. It is now a national monument.

Clark stopped here on the return trip before eventually rejoining the rest of the Corps where the Yellowstone meets the Missouri to the east, just across the Montana/North Dakota line. He named the formation after the nickname he had given Sakakawea’s son, and carved his own name into the soft sandstone formation. Scores of other travelers followed in wagons and then autos, carving their own names into the formation in the 19th and early 20th centuries before it became privately owned and the practice discouraged. We can thank the local Foote family, who managed the spot, for preserving his name under glass in the 1950s. The Pillar became a national monument in 2001. Let’s hope the efforts to preserve the formation will again allow visitors to climb stairs to view Clark’s signature.

Back On the Trail West

Okay, we’re back on the trail in Montana from Three Forks, so stay with me. We’re once again headed west, after a deep dive into an area where L & C spent a lot of time. Later, tales of spouting water columns and sulfurous air brought fame to John Colter, a member of the party, when he returned here a year or so later and was the first European to view Yellowstone.

Traveling west towards the Big Hole River brought one of the most fortunate meetings of their entire outbound journey. Sakakawea, who had been kidnapped from her tribe, remembered where her band of the Shoshone spent their summers near the present-day town of Dillon and another trout river they named the Jefferson.

It was there that, by a stroke of pure providence, Sakakawea recognized her brother, now the chief. They were reunited, and Lewis and Clark, now exhilarated, knew their path to the Pacific was more secure. The party knew they needed horses to traverse Idaho’s Bitterroot Mountains to the Columbia. The Shoshone, with Sakakawea’s help, provided not only horses but another guide.

They named the spot Camp Fortunate, and the day-use Clark’s Lookout State Park provides a vista of the area above the Beaverhead River, another trout stream. Camp Fortunate Overlook is above the spot where the meeting took place, now under Clark Canyon Reservoir.

Cross into Idaho via Lemhi Pass, if you have the gumption. Be advised that it’s a typical Forest Service high country dirt/gravel road with some steep grades, so go slow. There is no breakdown service at the top. Here are a couple of video previews so you can decide if you want to take your LTV up and over. This is also part of the 39-mile Lewis and Clark Backcountry Byway loop – you can pick up that loop on the Idaho side from the community of Tendoy, where it’s called Lewis and Clark Highway, or in Montana via Lemhi Pass Road off I-15.

About an hour to the north is the Big Hole, another great trout river, but unless you’re upstream in the area of Fishtrap Campground on the Big Hole’s banks, the fishing is best from a boat. You’re also close to Bighole National Battlefield, where the Nez Perce under Chief Joseph fought the US Army under Gibbon just 60-plus years later.

Heading from here towards Salmon, Idaho, you’ll be near where the American flag was first unfurled on the western side of the Continental Divide, and where it’s said Sakakawea was born. There’s a free BLM campground at Agency Creek on the highway in Idaho, and you can also relax in the small pools of Sharkey Hot Springs, another BLM site.

You’ll learn more at the Sakakawea Interpretive Center in Salmon, Idaho, before heading north back into Montana over Lost Trail Pass, where another interpretive center awaits. There’s more history to explore at Ross’ Hole, where the Corps rested before pushing on to a spot they named Traveler’s Rest, now a Montana state park. It’s about the only spot where you can absolutely say you’ve stepped right where they did, as artifacts from the journey were found here. Next, head toward Lolo Hot Springs, where they rested and bathed in the springs. You can do the same thanks to a resort and RV sites here.

Cross Lolo Pass on US 12, which is known as the Lewis and Clark Highway here, through the Bitterroot Mountains. (Another bit of Bill trivia: US 12 begins in downtown Detroit and stretches to the Pacific.) By the time the party got here, it was September, and like many LTVers have found out, snow comes early in the Rockies.

The Corps got lost in the Bitterroots crossing Lolo Pass (stop at the visitor center) and almost starved, only to be saved by the Nez Perce, who held council about what to do with the strangers. Again, a woman, this time a Nez Perce, interceded, and the party continued west.

Next stop: Canoe Camp. After making it over the Bitterroots, the Corps paused here to cache gear, give their horses to the Nez Perce until they returned, and carve five canoes out of trees in 12 days for the final leg of the journey that would bring them to the Pacific. The location of the camp is along US 12 near the Clearwater River, about 30 miles west of Nez Perce National Historical Park Visitor Center near Lewiston, Idaho. Camping is available nearby at Dworshak Reservoir near Orofino, Idaho.

They pushed on. Follow the route and you’ll pass Lewis and Clark Trail-Travois Road, where you can still see drag marks created by the travois that Native Americans used to transport gear between camps. You’re now approaching the Corps’ pathway to the Pacific, the Columbia River.

On October 16, 1805, the Corps of Discovery reached the confluence of the Snake and Columbia Rivers, another National Park Service historic spot. Their actual campsite is located within day-use only Sacajawea State Park (yup, different than the current accepted spelling). I’m sure their excitement rose when they saw Mount Hood (they knew it would be there) and could almost smell the end of their journey. Downstream is Oregon’s Hat Rock State Park (day use), the first rock formation the Corps saw on the river that was taking them to the ocean.

You’re now approaching the Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area, where you can stop at several visitor centers and camp along the river at forested sites like Wyeth or Eagle Creek, the first campground ever developed in the forest service system. Drive the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail, which accommodates vehicles as well as bike and foot traffic, depending on the route you choose. You’ll be driving the first scenic highway in the country. Or, drive I-84 at water level. Other places to stay include private campgrounds and, after crossing the river into Washington, Beacon Rock State Park.

Farther west is Oregon’s Sandy River (L & C called it Quicksand River for the large sandbar where it joined the Columbia) and Lewis and Clark State Recreation Site.

You’re now entering locations within Lewis & Clark National Historical Park. At Dismal Nitch, see where the Corps waited out a six-day November Pacific storm – not exactly the best thing to be caught in. The storm prevented them from reaching the last supply ship they knew would be there, but they pushed on. Cross the Columbia on the Astoria-Megler Bridge like we did, and reach campsites at Cape Disappointment State Park on the river’s Washington State side, near Ilwaco.

We walked the trails to the Cape’s lighthouse about 200 feet above the Park, overlooking roughly the same site as the overjoyed Corps of Discovery did in November 1805, when they saw the river mouth, the headlands, and the Pacific for the first time. The Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center here tells the story. No parking for RVs, unfortunately, but there are hiking trails to the Center.

A day or so later we crossed into Oregon at the bridge and immediately drove to Fort Clatsop, also part of the national park. When the Corps arrived here, their clothes were rotting off their backs. They threw together a log structure, and this is where they spent the winter. Today, a replica stands very near to where the original was located; that site remains secret. Other parts of the Park include the spot where the Corps landed their canoes before building Clatsop, the spot where they made salt from sea water to cure food for the return trip, and more.

Don’t forget to stop in Ilwaco at the local fishing docks. In season, you can charter a boat here to go after Pacific salmon. Local roads skirt the coast to other historic sites.

On November 16, 1805, the Corps reached the Pacific, ending the first half of their journey. You can follow the six-mile Fort-To-Sea Trail to Sunset Beach. The next half was the return, part of which we covered on this journey, especially in Montana. It was left to other explorers, including some who were in the Corps, to explore Yellowstone. They arrived back in St. Louis in September 1806.

In our own travels, we encountered Lewis one last time along the Natchez Trace. It was here that he mysteriously died in October 1809, after overnighting at a nearby inn.

But that’s fodder for another story. See you on the road for the telling of that tale soon.

When You Go

Great resources to help you plan include highlights of the route found at the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail website. The site includes a map of the Corps’ route west, then east, with historic sites marked along the way. Other resources include lewisandclarktrail.com and state and city visitor bureaus.

Because of possible COVID-19 restrictions, check to be sure tours and facilities mentioned are open.

Please note: The exact routes and roads described above were submitted to Triple E Recreational Vehicles by the author and have not been verified by Triple E Recreational Vehicles. Please do your own research on road conditions and road safety before attempting to drive these or other routes. Triple E Recreational Vehicles is not able to provide any information about road conditions or safety (including whether or not the scenic drives below are suitable for your specific vehicle). Always follow all applicable laws.

Comments