On our winter snowbird trip, we decided to visit Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge (aka Okefenokee Swamp) for two reasons: first, Sharon’s parents had visited it in 1966 and really enjoyed it, and second, we were having trouble getting campsites in the Florida Panhandle state parks in January. We were easily able to book 3 nights on the east side of the Refuge at Okefenokee Pastimes Campground, 4 nights at Laura S. Walker State Park on the north edge, and 3 nights at Stephen C. Foster State Park on the west side. This combination of campgrounds, covering 3 sides of the Refuge, gave us a great way to explore the different habitats. There was a quote I liked on one of the signboards that read, “If you reconnect with nature and wilderness, you will not only find the meaning of life, but you will experience what it means to be truly alive”.

Here are some fun facts about Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge:

- The Refuge was established in 1937 to protect one of the largest fresh water wetlands in the world. It also is a National Natural Landmark and is designated as a Wetland of International Importance.

- The Okefenokee Swamp is the headwaters for the Suwannee and St. Mary’s Rivers.

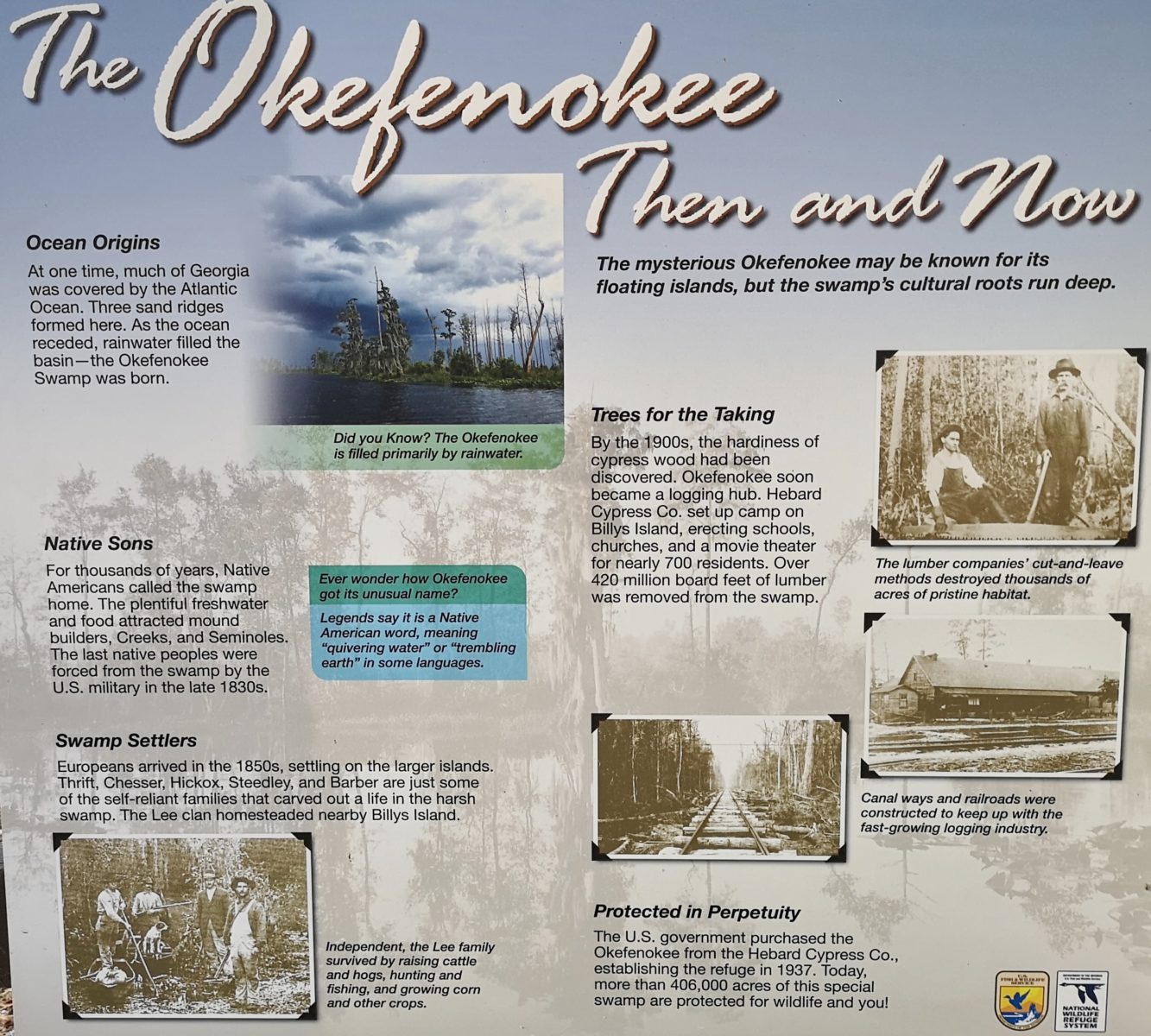

- The swamp bottom consists of sand covered by peat. Methane gas causes large clumps of this material to float up to the surface. Eventually, plant life will grow on the clumps, which are not solid as they are not anchored. The Native American Indians called this O-ki-fin-o-ke, or “Land of the Trembling Earth”.

- The Refuge covers 354,000 acres (61 km north-south, 40 km east-west) and is 1 of only 21 national wildlife refuges that has additional protection under the Clean Air Act.

- The swamp has many different habitats, including upland forests, scrub-shrub, forested wetlands, prairies (marshes), lakes, and open water.

- Within the Refuge you can find more than 620 different plant species, 230 bird species, 50 mammal species, 40 fish species, 40 amphibian species, and 60 reptile species.

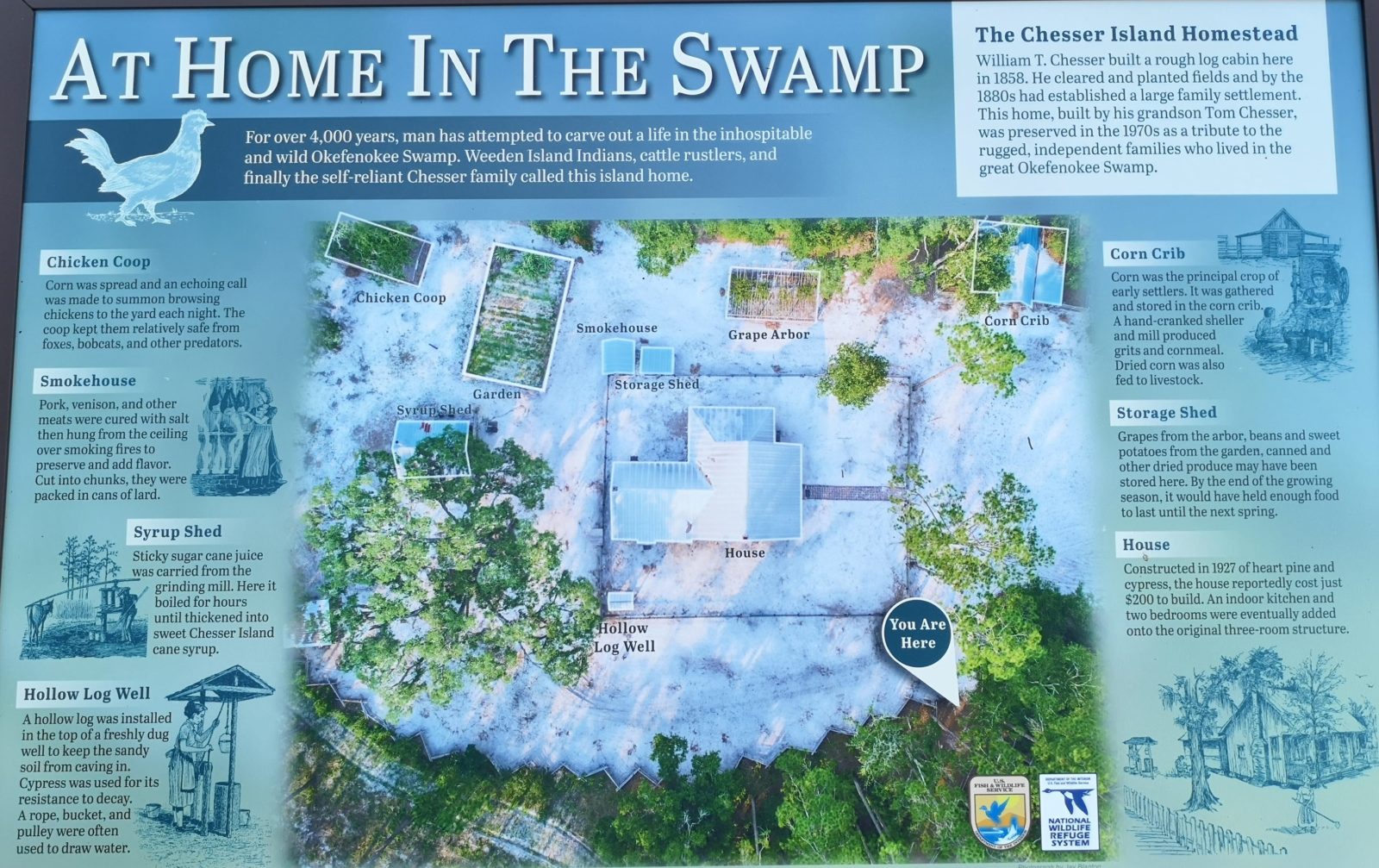

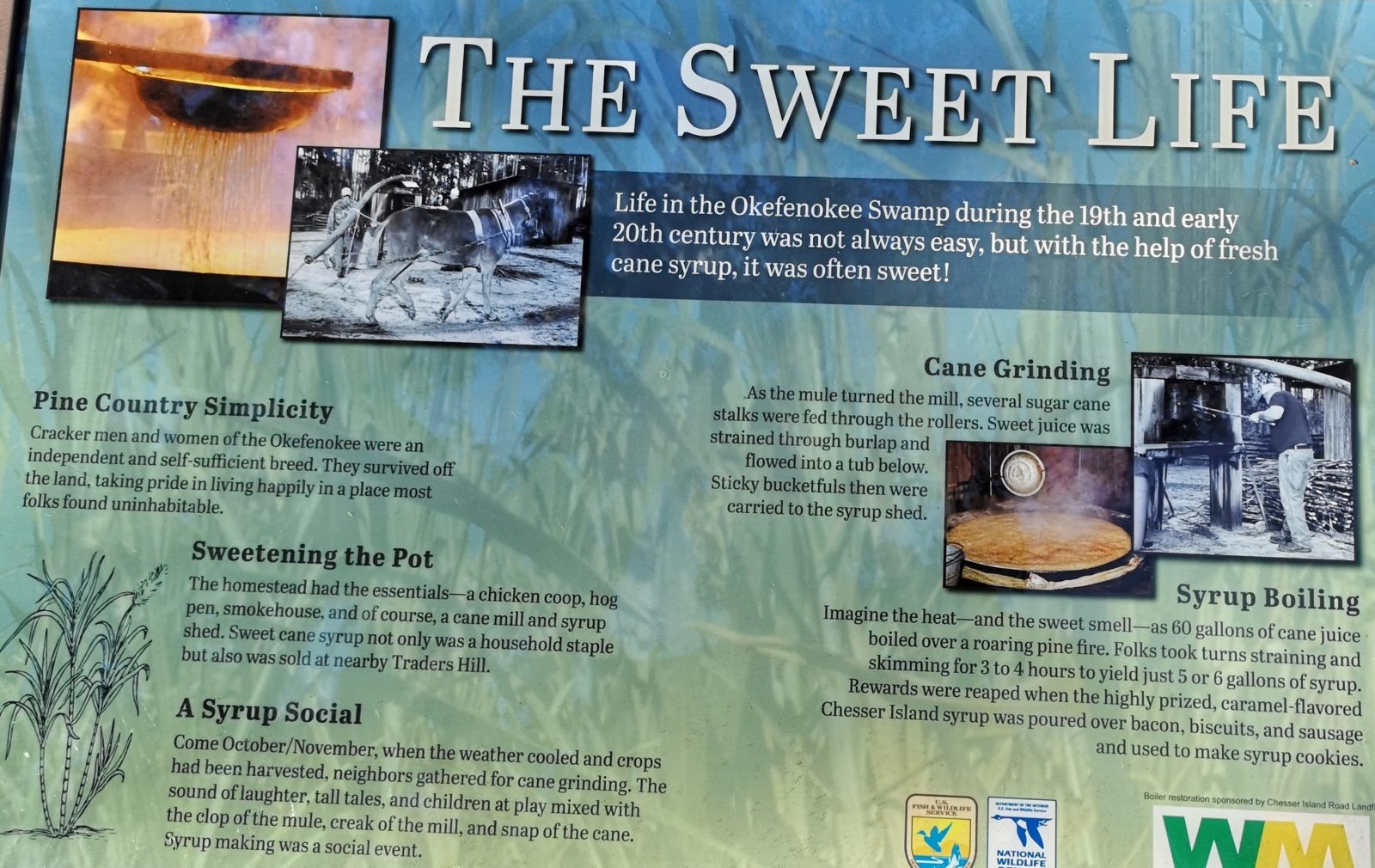

- Cypress trees have adapted to living in the swampy environment and have a life span of 400-500 years. Their wood is very resistant to deterioration and, consequently, in the 1890s there were attempts to drain the swamp to harvest the trees and create farmland. Canals were dug and attempts were made to put in railway tracks. Some early settler families also lived on some of the islands, raising livestock, growing corn and sugar cane, and tapping the pine trees for sap to make turpentine (they would sell this to get money to buy other supplies). Logging took place up until the Great Depression, before the area was declared a National Wildlife Refuge in 1937.

- The former logging canals now act as entry points for the 192 km of boat trails in the Refuge.

- The king of this swamp is of course the American alligator. The mother alligator will guard her nest; no other modern reptile displays this maternal side, but this was common behaviour for dinosaurs, which makes the American alligator seem prehistoric. It is estimated that there are 12,000 alligators in the Refuge!

Okefenokee Pastimes Campground is right at the eastern entrance to the Refuge. It is a small RV park with tightly packed sites, but it was very well-maintained, and we used our Passport America discount, so it was inexpensive. On our first day, we drove the RV into the Refuge and checked out the visitor centre, then took a 90-minute guided boat ride through the swamp. The guide gave us the history of the canal and explained facts about the prairies and forested wetlands, as well as the wildlife. We saw about a dozen alligators, but apparently you see many more when the daytime temperatures are higher (as we witnessed on the west side). We also saw several red-tailed hawks, turkey vultures flying overhead, yellow slider turtles, and a pitcher plant which attracts, traps, and then digests insects as a source of nitrogen! (There are 5 species of insect-eating plants in the United States, and 4 of them grow in this swamp.)

After the boat ride, we drove along Swamp Island Drive, stopping at the 12 numbered stops to read about the area. We learned about the longleaf pine tree restoration project that is underway. At one time, there were 90 million acres of longleaf pine forests in the southeast, and now there are only 3 million. The forest industry preferred loblolly and pond pines, as the longleaf pine grows much more slowly. Now, loblolly and pond pines are being cut down and replaced with longleaf, in order to take the Refuge back to its natural state.

There was a pond along the drive that had fantastic reflections. The pond was originally dug out to get the sand to make Swamp Island Drive, so people could get to where the Chesser Island Homestead was located.

The swamp settlers were self-sufficient and very industrious people. They grew sugar cane and harvested pine resin to make turpentine to raise cash. They also hunted, kept livestock, tended beehives, and kept gardens. Homesteaders in the area prided themselves on keeping a nice, white, sandy yard. Not only did this act as a fire break, but it also made the 5 venomous snakes of the area visible and kept the bug population down. The Chesser family settled in this area in 1858, and the third-generation homestead building, built in 1927, is still standing.

After seeing the homestead, we walked the boardwalk so we could climb the tower to see the Chesser Prairie and Seagrove Lake. We had to hurry a bit, as they close the gate for Swamp Island Drive at 5 pm, and a ranger was already doing his rounds to make sure everyone was out on time. On the way out, we got some great shots of a very large alligator who was sunning himself along the ditch beside the road. Earlier in the day, we were searching the water for alligators, and here we found one right by the road!

There are several trails in the Refuge, so the next morning, we got out our bikes and ventured out for a 31 km mountain bike ride. The first part of Longleaf Pine Trail was a bit wet, and it continued to get wetter as we proceeded. Swamp Island Drive was not busy, so it made for a very leisurely bike ride while searching out wildlife, and we went back to the Chesser homestead, since we were rushed the night before. We rode Homestead Loop Trail and Ridley’s Island Trail, before meeting up with our friendly alligator again on the way out. Alligators are creatures of habit; they tend to go to the same spots to sun themselves each day.

We saw some white-banded mature longleaf pine trees (at least 60 years old) on Uplands Trail, trees that the red-cockaded woodpeckers depend on. Loss of habitat is the reason this species is endangered. The red-cockaded woodpecker will only use live trees, because once they create their nest area, sap will drip out of the hole. Any predators will get the sap on their body and leave the tree, a good defense mechanism to protect young. We checked out some of the trees but did not see any of these woodpeckers, only the evidence that they were there. We did see several other woodpeckers (and heard lots) while in the Refuge.

To make our way back to the RV park, we used a combination of Canal Diggers and Longleaf Pine mountain bike trails, and the road. It was a long, strenuous day but very enjoyable, with perfect temperatures.

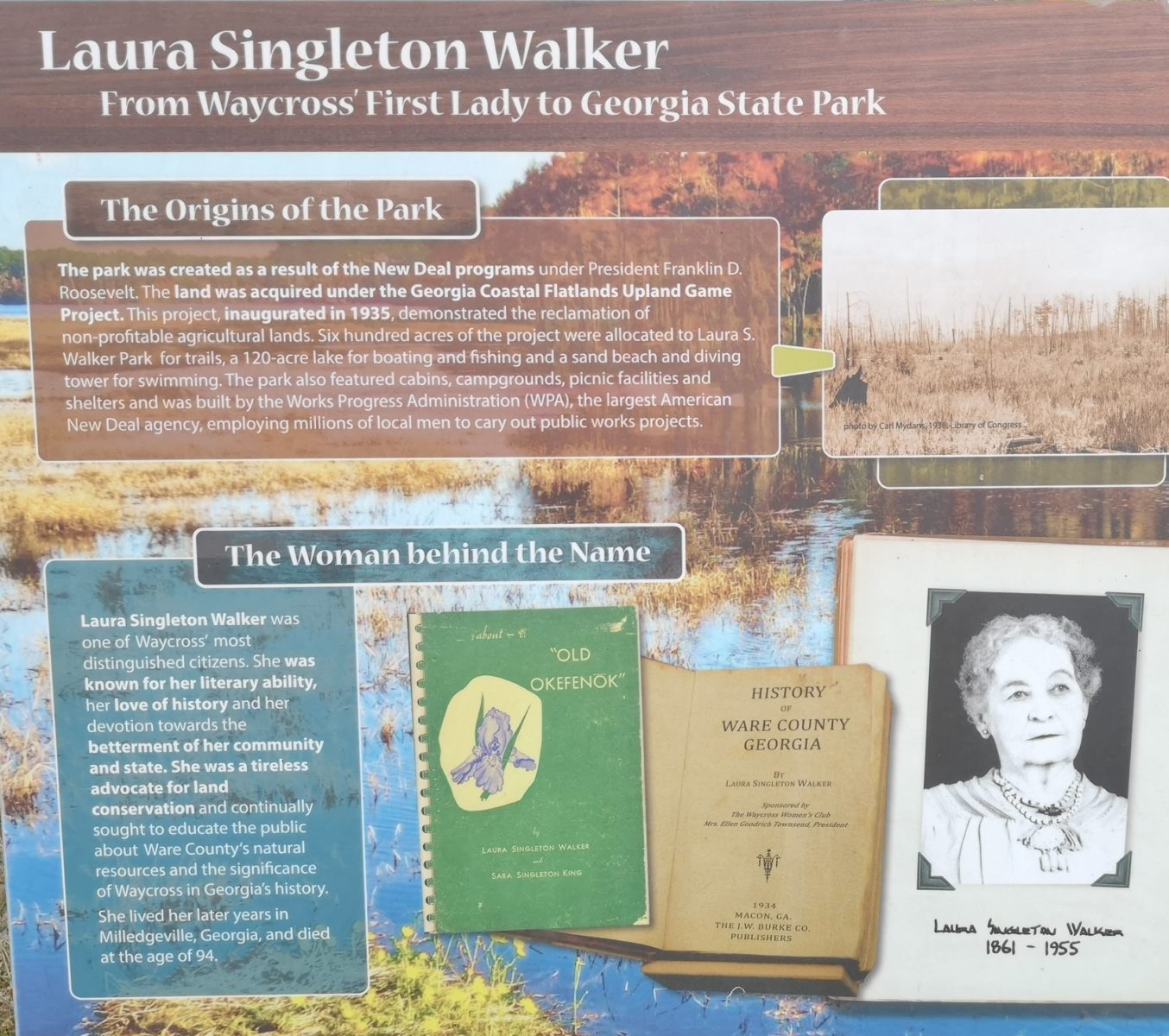

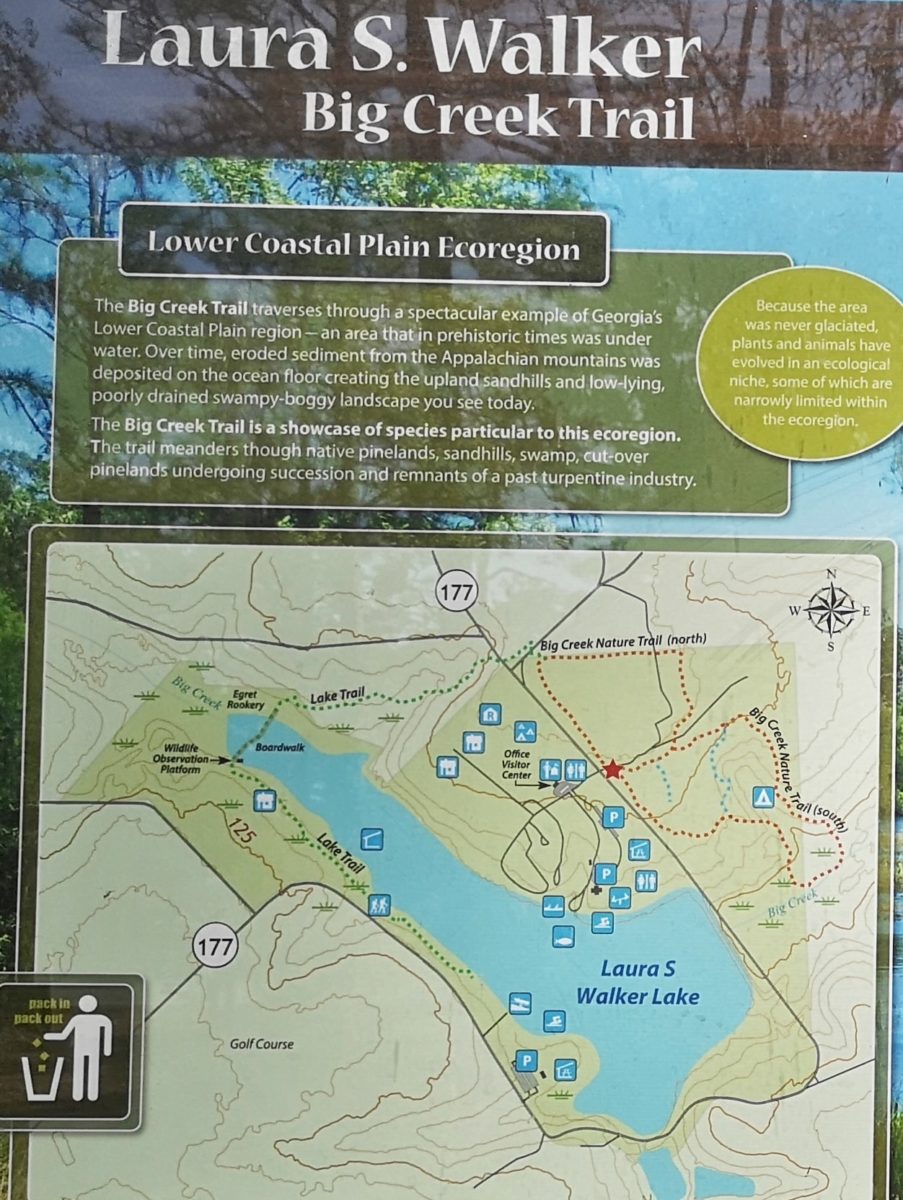

The following morning, we said goodbye to our new RV neighbours, Norbert and Christina from Germany, as they headed south and we headed north to Waycross, and on to Laura S. Walker State Park. We spent 4 nights in this Park, with a nice campsite overlooking the man-made lake. The Park is named after a very influential woman who was an advocate for the area and for conservation from 1861 to 1955. It was named Georgia’s 13th state park in 1941 – the first Georgia state park to be named after a woman.

Our first afternoon here, we walked around the campground to get oriented and enjoyed relaxing with our view of the lake.

There are lots of shared trails in this state park, so we got out the bikes and went exploring on the Big Creek Trail System and then Waterfront Trail, 13 km in total but with lots of stops along the way. We saw some “cat face” trees that had scars left by the turpentine industry, when sap was collected from these trees for 4 – 10 years before being harvested for wood.

The next day, we were back on the bikes for some more exercise, this time 17 km. This was a longer ride, since we ventured off the trails and onto the road to check out the golf course associated with the Park. On the way back, we stopped at the nature centre to check out the turtles.

On our last warm, sunny day, we traded in the mountain bikes for an aqua bike ride on the lake. We took the aqua bikes across the lake to the boardwalk and back in one hour. It was extremely hot wearing life jackets in the 88 degree weather! Luckily, all the motorboats came out on the lake after we were done.

It was time to move on to our last stop in the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge area, this time Stephen C. Foster State Park on the west side of the Refuge. Along the way, we stopped in Homerville at Mama’s Country Kitchen to try some southern fried chicken. This was a 27 km drive off the main road to the Park, but certainly worth the trip.

We were fortunate to have a winter heat wave while staying in this area, which meant LOTS of alligators out sunning themselves. Originally, we did not believe that 12,000 alligators could call the Refuge home, but after seeing all the gators in this area, we certainly believe it now! In one small area by the park office where the boat ramp was, we counted over 30 little gators hanging out. Of course, Big Momma (named Sophie) was not too far away ?.

This area looked like a great place to rent a kayak, but we decided we would first take the 90-minute guided boat trip to get the lay of the land. The trip was great, largely thanks to the park naturalist, who was very knowledgeable. We saw lots of alligators, a barred owl, turtles, cormorants, sand hill cranes, and great egrets. We learned that if you see an alligator with its mouth open, that means it is overheated and is trying to cool down. A group of adult alligators is called a congregation, and a group of babies is a pod.

The following day, we rented a tandem kayak just like the one we have at home, except it did not have a rudder so it was harder to steer. It’s quite disconcerting when you paddle by a 7-foot or 8-foot alligator and he slips into the tannin-colored water – once he goes underwater, you don’t know where he is!

We first paddled along the same route (Billy’s Lake) that the tour boat followed the day before, but then we took the Minnie’s Lake channel, which was very pretty. There was one narrow section called Pinball Alley, where you feel like a pinball as you turn around all the large cypress trees in the water. We saw similar wildlife to the day before, except we also saw some white ibis. However, the peacefulness of gliding quietly along the water gave a very different experience than when on the tour boat. We covered about 8.5 km in 3.5 hours of paddling. Sharon commented, “This is what I always thought the swamp would be like.”

That concluded our visit to Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge in Georgia, and we were really glad we did this side-trip off the coastline. It was easy to get campsites at all 3 parks in January, and we had great weather, which allowed us to see lots of wildlife. In addition, with our Georgia State Park pass, we were able to take advantage of their January 50% off camping special, which meant it was very inexpensive. Another great place to add to your travel bucket list.

Comments