Editor’s Note: This post is written by a member of LTV’s sponsored content team, The Leisure Explorers. Do you own a Leisure Travel Van and enjoy writing? Learn more about joining the team.

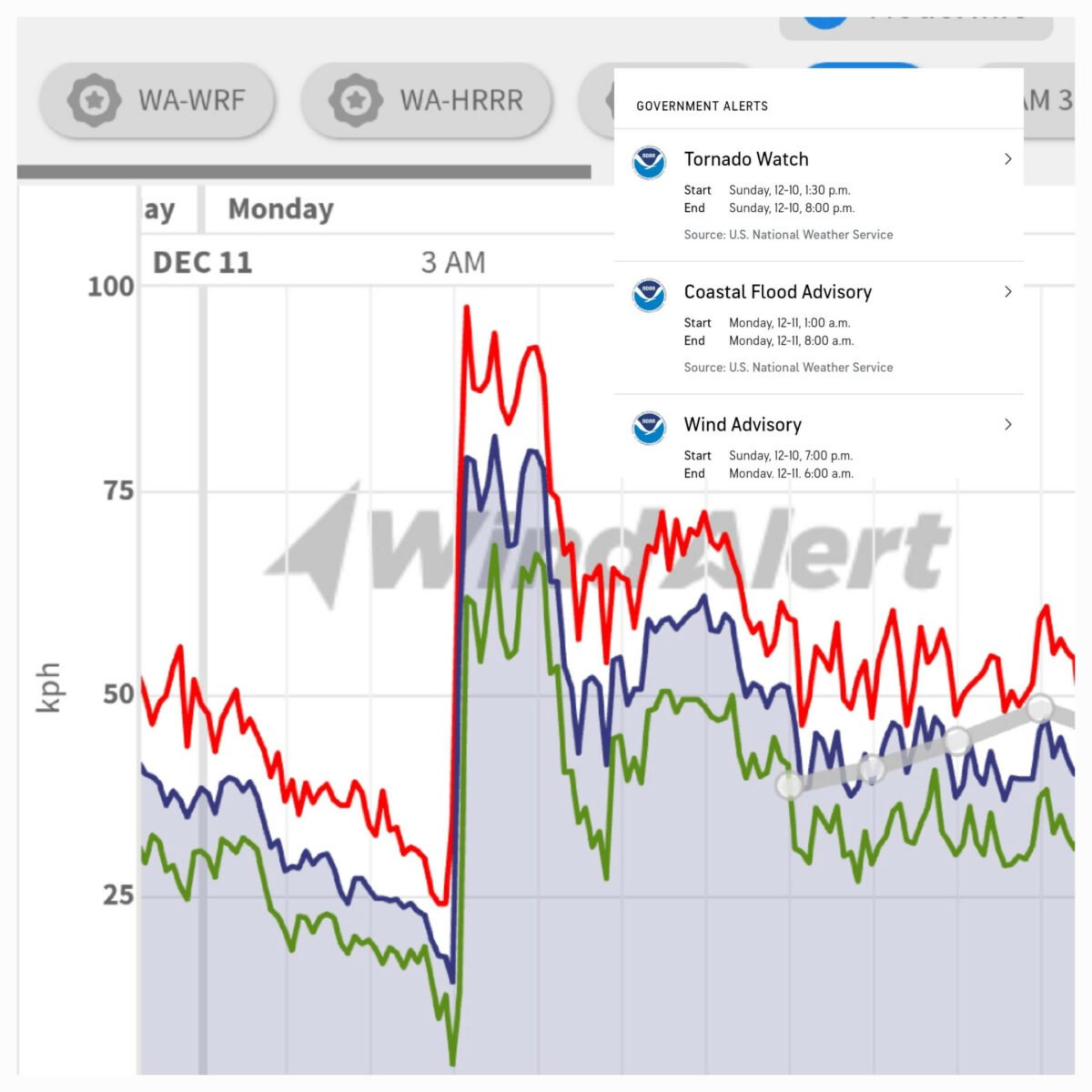

Our first stop in the Outer Banks as we headed south last December was Oregon Inlet Campground, part of Cape Hatteras National Seashore. We had booked into Oregon Inlet for six nights to see various things in this upper area of the Outer Banks. The next evening, we had incredibly scary winds at 3:00 am. We both woke up as the RV was shaking back and forth. I told Sharon we better put everything loose away and close all the cupboards in case we get toppled over on our side. You’ll see from the weather chart that we hit peak gusts of 98 kph winds and were in a tornado watch, a coastal flood advisory, and a wind advisory! We didn’t sleep much for the rest of the night.

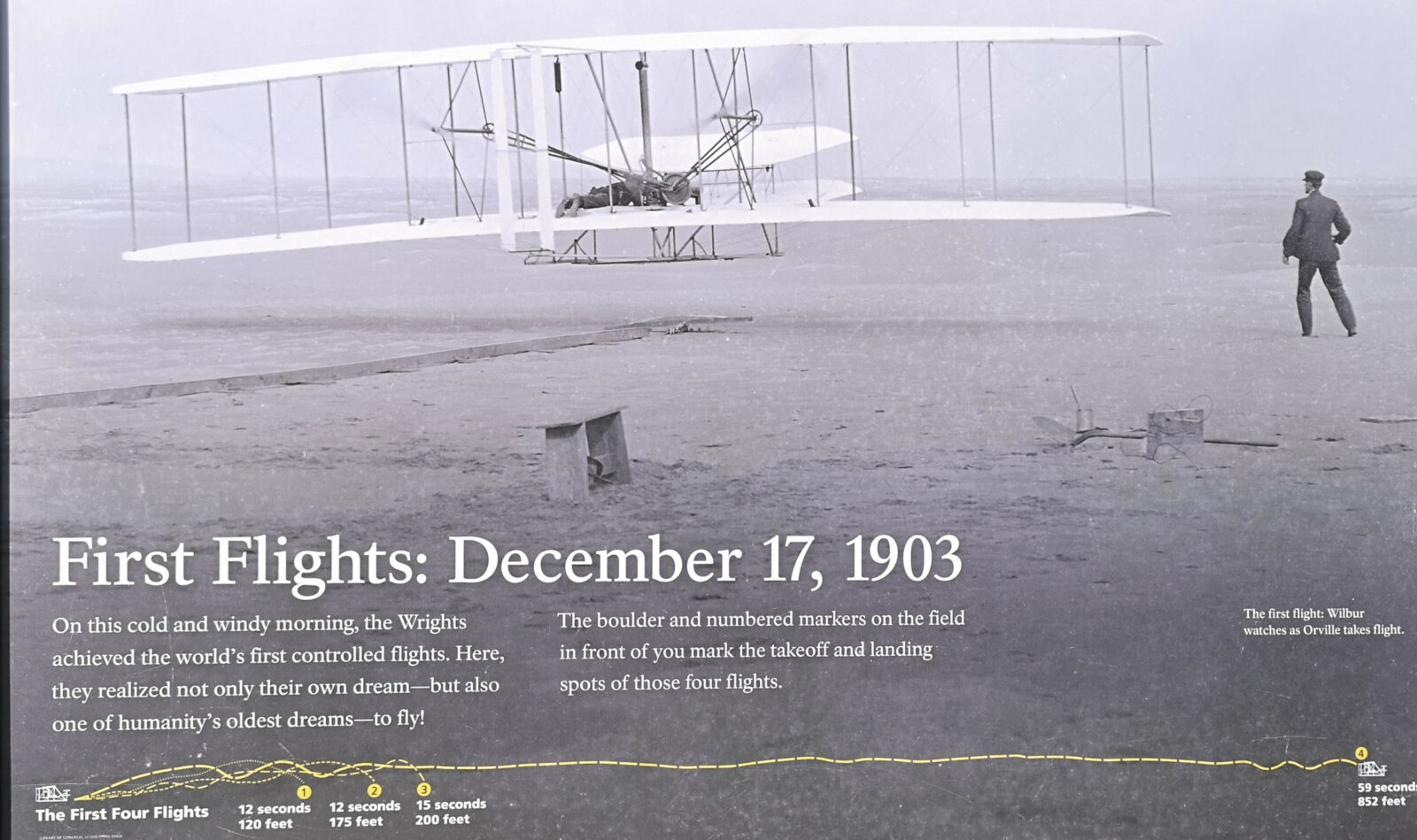

The next day, we drove north to see the Wright Brothers National Memorial. We started with the museum and then attended the ranger talk on the brothers. After the museum, we walked out to see the reconstructed quarters, hangar buildings, where they took off, and the landing points for the four flights in 1903. Then we walked up to the top of Big Kill Devil Hill, where they tested gliders in 1901 and 1902, where the monument is located, and lastly to the brass sculpture of the 1903 event. Here are some fun facts about the Wright Brothers:

- Wilbur and Orville grew up in Dayton, Ohio. Their mother, Susan, was a college graduate and mechanically minded, and their father, Milton, was an ordained minister. Their parents encouraged them to test their wings and pursue their dreams. The family had seven children.

- Wilbur was older than Orville and was intelligent, quick-witted, could retain facts, and put things in a logical order. Orville was a dreamer, idealist, restless thinker, and sharp dresser. Like his mother, he was mechanically minded and could see why something wasn’t working and how to fix it to make it better.

- One day, Milton brought home a helicopter toy that Wilbur and Orville called the bat, which started their obsession with how things could fly.

- The boys’ first business was publishing an African American newspaper called the Dayton Tatler in 1890. They also saw how popular bicycles were becoming, so they started a bicycle repair business, which provided them with bicycle parts they could use for their gliders and flyers.

- Between 1891 and 1896, Otto Lilienthal (the world-famous “Flying Man”) made 2000 glider attempts but died in an accident in 1896. His death restarted Wilbur and Orville’s interest in flight, so they started to study how they could fix the issues that caused Otto’s death.

- Many people were attempting flight at this time, but the Wright brothers were the first to pursue how to design control into their flyers instead of concentrating only on power.

- To choose a destination to test their flying machines, they contacted the National Weather Service to find the country’s windiest places. Chicago was number one, but they wanted a small place, and Kitty Hawk was number six on the list, with only 60 people living there, so they chose that location. From Dayton, they had to take a train, then a boat, then a train, and again a boat with all their plane parts each time they went.

- The sequence was a kite in 1899, a glider in 1900, a bigger but not better glider in 1901, a record-setting glider in 1902, and the flyer in 1903.

- Four problems had to be solved to reach the final goal of powered flight. Problem number one was lift. They used a wind tunnel to design the right-curved wing shape that generated the most lift and the least drag.

- Problem two is control–they developed their axis control (roll, pitch, and yaw). The wings and hip cradle control roll, the elevator in the front of the flyer controls pitch, and the rudder at the back controls yaw.

- Problem three: Thrust–the propellers generate horizontal lift, acting as thrust. The breakthrough was their propeller design, wings spinning in a circle. The flyer had two propellers spinning in opposite directions to counteract torque.

- Problem number four: Power–the engine provides the power, but it is unlike any other engine ever built. It was lightweight, made of aluminum, and had four cylinders, producing 12 horsepower.

- On December 17, 1903, they completed four powered flights. Flight one, Orville, travels 120′ in 12 seconds; Flight two, Wilbur, goes 175′ in 12 seconds; Flight three, Orville, travels 200′ in 15 seconds; and Wilbur flies 852′ in 59 seconds. They went into the hangar to celebrate and were going to try other flights, but when they came back out, major winds had come through and damaged their plane beyond repair.

- In 1969 when mission commander Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon’s surface, he carried fragments of the 1903 flyer in tribute to the Wright brothers.

What baffles me about this whole sequence of events is how the Wright brothers could afford to do all this trial and error to reach their goal. I asked the park ranger who had initially done the presentation, and she said the brothers were extremely frugal and had very few outside activities that they spent their money on. This, combined with the money they made with their bicycle repair shop business and the fact that they had access to many of the parts they needed from the shop, helped them pursue their dream. You can make the impossible possible by following your passion and pursuing your dreams.

Heading back to the campground, we decided to stop at the Bodie Island Marsh Blind, where we saw a flock of Tundra Swans feeding. Then we stopped to see the Bodie Island Light Station, and our timing was perfect for getting some beautiful pictures of this lighthouse during the golden hour. The current lighthouse was the third one built. The 1847 lighthouse was abandoned because it had a poor foundation. The 1859 one was blown up in 1861 by the Confederate troops because they were worried the Union troops would take advantage of the lighthouse for navigation. The current lighthouse was completed in 1872 on the north side of Oregon Inlet and stands 150 feet high. You can see the beam of light 19 miles into the ocean. The lighthouse wasn’t open to climb, but we did a short hike to a lookout and enjoyed the setting sun.

The next day, we headed out to Jockey’s Ridge State Park. This park has the tallest natural dune in the eastern United States, with heights from 60 to 80 feet; it’s constantly moving. In the winter, it moves northeast, and in the summer, southwest, so it just blows back and forth. At one point, a development was going on in this area, but a woman blocked the developer, and then eventually, the state bought the land and created Jockey’s Ridge State Park. It’s a fun place to walk the dunes and explore. We did the Tracks in the Sand trail to Roanoke Sound, then we went up to the top of the ridge, and the Park Ranger told us we could just walk over the dune to get to the Soundside Nature Trail. Some fun facts from the visitors’ center:

- The dune sand is mostly quartz and is beach sand washed up from the ocean and blown across the land. Obviously, both the Wright brothers and we have seen how strong the winds can be in the Outer Banks!

- We found many tracks in the dunes and were trying to identify which animal had left them.

- The park’s main feature is the sand dunes, but there are also mature maritime forest areas with live oaks and pines.

- The beach is a buffet of marine worms, mollusks, and crabs for shorebirds.

- Grasses grow on the front side of the dune, whose roots stabilize the dune and then give way to shrub thickets.

- The Outer Banks can be as narrow as 150′ or as wide as 5 miles.

- Between the shrub thickets and maritime forests, pockets of fresh water can collect, providing a refuge for animals.

- On the back side of the barrier islands, the sound shore and grasses provide a healthy habitat for juvenile fish, crustaceans, and mollusks.

- The shore is called the Graveyard of the Atlantic, as an estimated 3000 ships have sunk due to strong currents, diamond shoals, hurricanes, and war activity.

There was a hang-gliding school in the park, but it was a three-hour course, so we opted not to take it. If they had an option where people would take you for a ride, I might have tried it. Also, on the ocean side of the dune, there were remnants of a mini golf course that had been abandoned and was now buried in the sand. Instead of taking the highway back, we took the beach road to check out all the houses. Nags Head is a tourist destination. We also stopped in to see the fishing charter area across the road from our campground.

The next day, we headed to Roanoke Island by taking a bridge from Bodie Island; our destination was Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. We arrived just as an interpretive tour was starting. Here are some fun facts:

- 1584–Sir Walter Raleigh sponsored the first exploration and settlement of the North American coast with a charter from Queen Elizabeth. The English were welcomed by the Algonquians on Roanoke, and when they departed, two Algonquians came with them to England (Manteo and Wanchese). The report back to Raleigh was a positive one.

- 1585–Raleigh sent seven ships with over 600 military people in hopes of occupying the land for England. Artist John White came along to record pictures of the expedition. With limited supplies, the military depended on the Algonquians. However, several were dying due to the European diseases brought on the ships. Trouble was brewing, and when replacement supplies didn’t arrive on time. The men went back to England with Sir Frances Drake, while only 15 stayed to maintain England’s foothold in America. The earthen fort structure was built during this time.

- 1587–Trying to create a true colony, 117 men, women, and children were on the next voyage. They hadn’t planned to colonize Roanoke but further north near the Chesapeake Bay. However, when they stopped to look for the 15 men left behind in 1585, the ship’s captain refused to take the colonists further. The Algonquians remembered the bad treatment they received, and things were deteriorating, so the captain returned to England for supplies, leaving the colonists. However, White and his ship weren’t allowed to return as all boats were needed to fight Spain. When he did return in 1590, no colonists could be found. They became known as The Lost Colony of Roanoke.

- The first child of English parents was born in America on August 18, 1587, and her name was Virginia Dare. The county is named Dare after her, and many businesses also use the Dare name.

- 1862–Civil War Union forces take over Roanoke with 13,000 troops on the island. Word spread that Roanoke was a haven for enslaved workers. Hundreds arrived, and the army established a Freemen’s Colony. By 1865, 3500 people were in the colony, but that dropped to 950 in 1867 when landowners reclaimed their land. The Freemen had less area to farm and faced starvation, so they left the area.

- 1902–The first human voice using wireless technology was transmitted by Reginald Fessenden. Wouldn’t he be surprised at wireless technology today?

After the guided tour, we spent time in the museum, which had lots of displays. Then we walked around the grounds and the nature trail and saw the open-air theatre. This theatre has been performing a show called The Lost Colony since July 4, 1937. It is now the longest-running outdoor drama in the United States. A few days later, our waiter at a restaurant said he had been one of the cast members.

As we left Fort Raleigh, we stopped at the Coastal North Carolina National Wildlife Refuges Gateway. It was very good, with a small theatre and a helicopter flight simulator to fly you over the area. The closest refuge was Alligator River, and the ranger said we could see lots of Tundra Swans as they flood the fields, so they could stay at this time of year. We decided we would check it out the day after as the sun would soon be setting; part of the challenge at this time of year is the early setting of the sun. The refuge is also home to alligators, black bears, and red wolves. The following day, we drove over the bridges to get to Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. We started with a short trail along the canal system and then went on the Wildlife Drive loop dirt road. We saw lots of Tundra Swans in the first field, but then we drove west, and in another field, the Tundra Swans were even closer. Next, we did the Sandy Ridge trail, where we saw signs of the beaver but not the actual beaver. We also got a view of Sawyer Lake. After exploring for the morning, we decided to go to Stripers Bar and Grille for another seafood lunch. I tried a Michigan Kalamazoo Stout and a local Highland Brewing Oatmeal Porter. We had a crab rangoon appetizer, and I had the lemon pepper Flounder topped with crab meat. Sharon had Grilled Scallops—excellent lunch in a local type of place with a great view.

Our last stop before returning to the campground was Jennette’s Pier. This location is famous for being a place for people to pay to fish off the pier, but we were there to see the aquarium displays they had inside. The pier had originally been built in 1939 but then it was destroyed by hurricanes in 1960 and 1962, and then purchased by the NC Aquarium Society in 2002, only to be destroyed again in 2003. In 2008, rebuilding began and was completed in 2011 to hopefully survive future storms. The aquariums explained about the Sealife that lived around the pier with sample tanks and even live underwater cameras. They also do a lot of Plankton research here, which was interesting to us since we had named our RV Plankton–drifter at sea. The pier is also the home to a complete weather station, where we had been getting our local weather data.

We had been closely watching the weather forecast, and a serious storm was moving its way up the coast, and the prediction for Sunday was for wind gusts topping 124 kph. Since we had seen the prior Sunday how bad 98 kph was, we didn’t want to experience this storm anywhere on the Outer Banks. That evening, we modified our plans to go south and decided instead to go inland since the winds would at least be more manageable there. This meant on Friday, we would tour Pea Island and then move inland on Saturday for three nights to let the storm and the aftermath get dealt with. As we found out later, this was the correct decision.

We crossed over a long high bridge to reach Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, a midway point on the Atlantic Flyway for numerous waterfowl. The island got its name from the small flower that grows and creates a bean, which they called dune peas. These provided the birds with lots of nourishment. The name Pea Island stuck. Our first stop was the Oregon Inlet Life Saving Station (operational from 1874 to 1954), which the historical groups are trying to raise money to restore. We decided to take a walk along the beach to look for shells, and as we progressed, we saw a dead Burrfish, lots of jellyfish, and a couple of marker buoys. Further down the beach, it looked like a sailboat had run aground in the sand, and an excavator was trying to remove it. As we got closer, we realized a crane was there, and they were trying to hoist the sailboat onto a huge flatbed truck. We read later that the sailor was from Connecticut and had just purchased the boat. He was heading south and ran out of fuel, lost power, couldn’t reach Oregon Inlet, and then ran aground. To recover the boat, they winched it ashore into the dune and then dug out the dune to hoist it onto the truck. It turns out this happens all the time along the Outer Banks. We watched with fascination as the whole process unfolded and realized later that the owner was there helping the recovery crew. Here is a link to the article: Grounded Sailboat Recovered.

Pea Island is a birder’s paradise with over 365 different species passing through or staying for the winter. We looked at some tundra swans through the scope in the visitor’s center and chatted with the 30-year volunteer. Then we walked around the pond, but many birds were in the distance, so we had better views of the Tundra Swans at Alligator River. Across the highway, you could climb over the dune and see a shipwreck boiler out in the water. We also saw a few dolphins cruising along the coast.

Our inland destination to avoid the storm was Goose Creek State Park for three nights, and then we returned to Oregon Inlet to proceed on our Outer Banks journey by heading south on Highway 12 to Cape Hatteras. We had been monitoring the reports on the storm damage, and Highway 12 was closed for one day as they cleared the sand and water from the 14’ storm surge that had breached the dunes. However, the road on Ocracoke Island had been closed for three days, so the ferry had not been operating. Luckily, they opened late Tuesday, and we planned to take it on Wednesday. We got lucky with rebooked timings. We had already seen Pea Island, so our first stop south was in Rodanthe, where we saw the Chicamacomico Life Saving Station. Unfortunately, the museum was closed for renovations, but we could at least look outside the buildings. We saw the 1874 station that was the first in operation in North Carolina; in total, there were 29 life-saving stations built 6-7 miles apart. The 1911 station was much larger, with a cookhouse, a boathouse, a tractor shed, and a 2-horse stable. It also had two water tanks and a water cistern. The site was converted to the U.S. Coast Guard in 1915 and saw action in both WWI and WWII before decommissioning in 1954.

As we continued south on the Outer Banks, we went through small towns like Waves, Salvo, Avon, and Buxton. They were all touristy but not as populated as Nags Head. In Buxton, we turned off to visit Cape Hatteras Light Station. Here are some fun facts about it:

- The first lighthouse was a 90-foot sandstone structure built in 1803, but the light didn’t travel far enough, so in 1854, it was extended to 150 feet with a first-order Fresnel lens.

- In 1861, retreating Confederate soldiers took the Fresnel lens so the Union soldiers could not use it.

- Shell damage during the war prompted the construction of a new lighthouse in 1870, which is still standing today.

- Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is America’s Lighthouse, the tallest brick beacon in the country at 198′.

- Beach erosion threatened the lighthouse in 1935, so a temporary tower was set up. The Fresnel lens was damaged in 1940, and the lighthouse was electrified with two active 1000-watt lamps that can be seen for more than 20 miles.

- In 1999, the lighthouse was moved a half mile inland over 23 days on railroad tracks to prevent further erosion.

- The original base stones were saved and can be seen by the visitors’ center. Work is currently underway to restore the Double Keeper’s and Principal Keeper’s quarters.

When we were there, the lighthouse was closed for climbing, so we enjoyed it from ground level.

After the lighthouse and Buxton, the Outer Banks start to turn southwest. You go through Frisco and Sandy Bay, and that’s where we saw the worst of the road conditions. We had to drive through salt water on the road (not the best thing for the vehicle) and through sand areas they were still clearing, along with repairing power lines. Once in Hatteras, we stopped to see the first stand-alone US Weather Bureau Station that was operational from 1902 to 1946. Again, this is more off-season, so it wasn’t open to visitors.

We were taking the free ferry from Hatteras to Ocracoke Island, and we arrived early, so we were second in line to get on the ferry. We chatted in the terminal for a long time with the ferry attendant, who told us several things to see as we continued our journey south. Since we had time, we decided to walk over to the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum which was just across the parking lot. Unfortunately, it was closed for renovations, so we could only look at the outside exhibits. One of the most famous wrecks was the USS Monitor which was an ironclad ship used during the Civil War, it sank on New Years Eve of 1862. After looking at the outside exhibits, we took a stroll on the beach but had to clean the bottoms of our shoes as they were full of sand spurs from the grass around the museum. The sand spurs are incredibly sharp, so you don’t want to bring them back into the RV!

The crossing to Ocracoke Island is not that far in the distance, but the ferry must follow the dredged channel, so it takes about an hour. Once on Ocracoke Island, we could see why the road and ferry had been closed for three days as they were still clearing sand off the road! The distance from the Atlantic Ocean to the bay side was minimal, so the storm surge would be easy to wash over the dunes. They even had sand-filled sacks at the base of the dunes to try to protect them, but the front-end loaders were actively trying to pile the sand back up onto the dunes.

Before reaching the Ocracoke Campground, we stopped to see the Ocracoke Pony Pasture. Ocracoke has had wild horses since the 1730’s. Once the highway was put on the island in 1959, the National Park Service corralled the ponies to protect them from cars on the road. Due to the rise in sea level, the park has lost many acres of the corral area, so they are studying what they should do next with the horses. When we first watched the ponies from the viewing platform, they were in the distance. However, we walked across to the beach on the other side of the road and looked for some seashells, and then when we returned to the corral, the horses were feeding right by the platform. We continued to the campground, where we had an excellent site with no services. Ocracoke Campground is right on the beach, so you have to climb up over the dune, and you are there. The far end of the beach faces west, so you get fantastic sunsets over the island’s tip. We stayed on Ocracoke for three nights, and all three had incredible sunsets.

The next day, we did the short Hammock Hills Nature trail (across the road from the campground), and we were surprised at how large the dune hill was climbing up into the pine forest. This barrier island is like the others where you go from beach to dune, then maritime forest, and lastly to salt marsh. The nature trail had display boards explaining the vegetation in each of the zones. The coolest thing we saw was a large Golden Silk Orb Weaver spider. After the nature trail, we walked along the beach where we saw a Mermaid Purse, a Reticulated Cowrie Helmet shell and offshore we saw a large flock of Cormorants flying in a line and a fishing boat. That evening, we had an even more spectacular sunset.

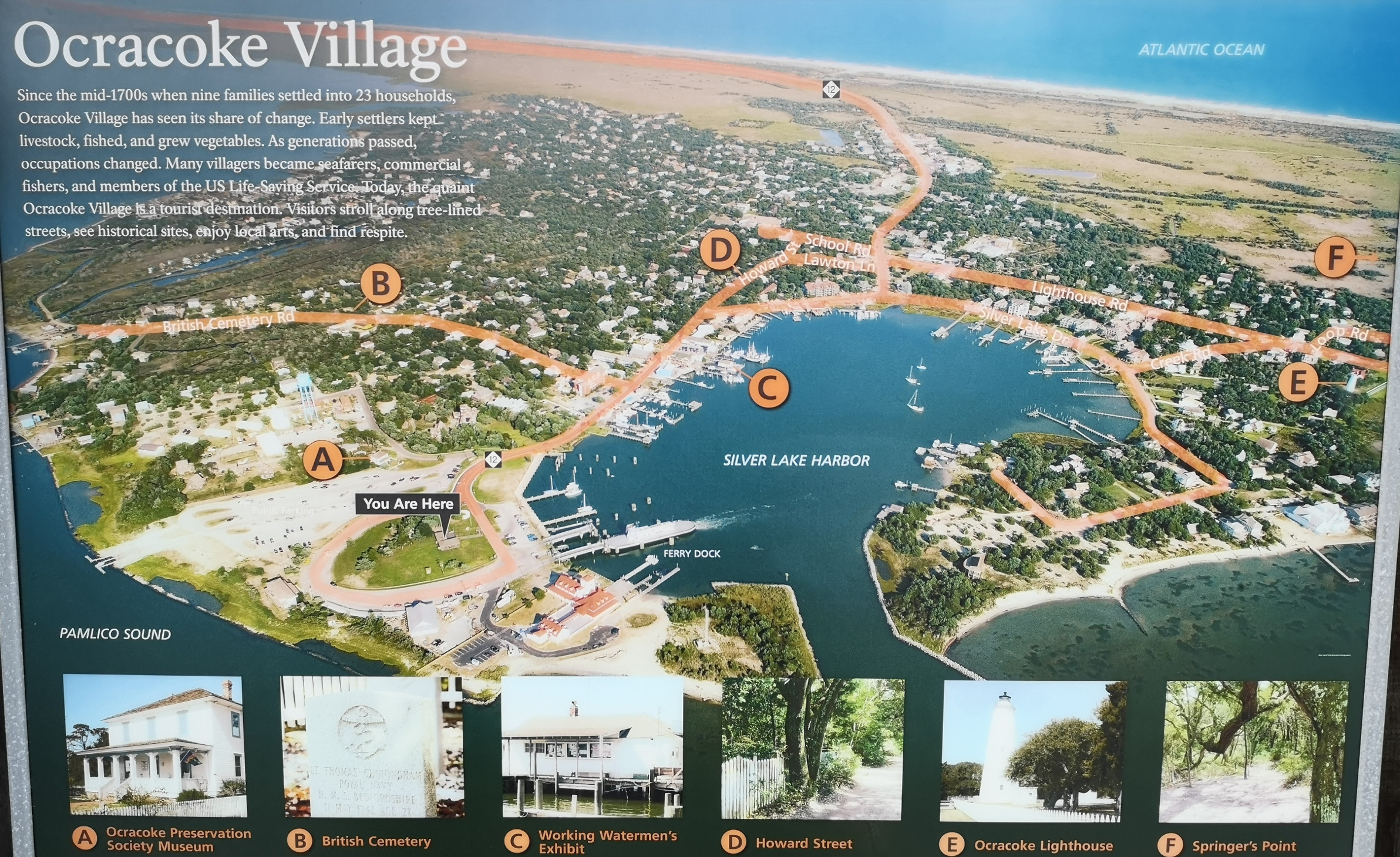

For our last full day, we drove into Ocracoke village to look around. Our first stop was the Ocracoke Lighthouse which is the oldest functioning lighthouse in North Carolina. It was constructed in 1823 and stands 75’ tall and guides ships through Ocracoke Inlet. In 2019 Hurricane Dorian flooded the Light Keeper’s house so it wasn’t open to the public. A restoration project is underway to raise the station 4’ and that is supposed to be completed by 2025.

After the lighthouse we parked by the ferry terminal and walked around town to see the historic sites as well as do some shopping at the kite shop and the local thrift store. One of the historic sites was the British cemetery where 4 British sailors from the HMT Bedfordshire were buried after dying in WWII anti-submarine patrols. Their ship was torpedoed and sunk by a German sub, and all were lost. Only these four bodies were recovered.

Our last stop in town was 1718 Brewing, connected with Plum Pointe Kitchen for some beers and lunch. I decided to have a beer flight which included Frontside Grind West Coast IPA, Rye-Toid Red Ale, Badda-Boom Bourbon Barrel Aged Strong Ale, You Better Watch Out Belgian Tripel, and lastly, Oyster Stout, which was filtered through oyster shells so you couldn’t have a shellfish allergy to have this beer. The beers ranged from 6.1 to 10.5%, so we opted for Sharon driving back to the campground. For lunch, we had spicy cheese curds as an appetizer, and then I had the blackened flounder, and Sharon had the shrimp tacos. Great beers and a great meal!

That evening we had another lovely sunset, each night very different from the others. Sharon woke up early the following morning and got a sunrise photo. Then we drove into Ocracoke village again for a walk around before we boarded the ferry to head to Cedar Island. The ferry crossing from Ocracoke to Cedar Island takes about 2 hours, and this one costs $30 for our RV. Cedar Island is called the “Down East” portion of the Outer Banks. There was an RV park called Cedar Island Ranch RV right when you got off the ferry, so we decided to stay there through Christmas since the state parks were all closed. We had an excellent experience walking the beach on the property, seeing a dozen wild horses feeding and staring at us, wondering what we were doing. Eventually, they wandered off the beach, and we figured they likely crossed the shallow channel to get to an uninhabited island. A camper later told us that many of the wild horses were drowned in a hurricane several years ago, but the herd is starting to recover. Down East was an excellent location to pause and reflect on our great adventure along the North Carolina Outer Banks. You just need to be aware that storms can cause disruption for travel along Highway 12 and with the ferry crossings. Stay flexible and drift with the current like we do with our RV Plankton.

Comments